A huge impediment in electric vehicles featuring in significant auto sales in India is the woeful shortage of charging points. While publicly accessed fast charges have stagnated for the past three years at 25 locations that of the slow chargers have gone up from 225 locations to 325 from 2018 to 2019. As is the wont of this government, Union Minister Nitin Gadkari made tall claims like India would be driven on electric by 2030 without the vaguest notion as to how that will be possible.

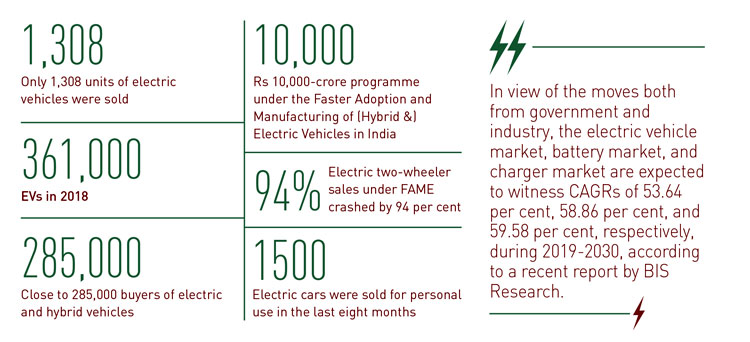

Despite all the hype and hoopla of the Union government, only 1,308 units of electric vehicles were sold in the first eight months between April and November FY20. It is to be noted that EV made a mere 0.07 per cent rise of total passenger vehicle sales, which was 18,82,047 units.

Electric vehicles had their biggest year ever in 2019, even as storm clouds gathered over their future. The numbers were huge. Automobile companies committed $225 billion to electric vehicles in the coming years. Electric vehicles (EVs) took over 2.2 per cent of the global market over the first 10 months of 2019 as a slew of new models hit the road. Ford displayed its upcoming electric Mustang Mach-E (a crossover SUV) and an electric F-150 pick-up. Tesla, however, shocked everyone by turning a profit and previewing an interesting future with its “cybertruck,” potentially the Hummer for Millenials.

But it wasn’t all hunky-dory. Apart from China and Norway, where car buyers enjoy generous incentives, the market is still driven by early adopters rather than the mainstream. EV sales for the year have been rather slow. While some US states like California have seen EVs capture eight per cent of new sales, the rest of the country has not yet caught on. After doubling between 2017 and 2018, EV market share in the US had crept up very poorly from 1.6 per cent last March to 1.8 per cent a year later.

After selling a record 361,000 EVs in 2018, automakers forecast a robust 2019. Yet for carmakers other than Tesla, sales sputtered out mid-year. Sales for the three dozen or so other EV models on the market declined by around 20 per cent in 2019 compared to 2018, while Tesla’s Model 3 sales tripled between January and September. Tesla represented an astonishing 78 per cent of US EV sales as of October delivering about 123,000 Model 3s, and 30,000 Model S and Model X vehicles. But EVs proved to be a rare bright spot amid what appears to be a long-term decline in global auto sales now entering its third year.

Till December 2018, there were about 5.3 million light-duty all-electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles in use across the world. Despite the rapid growth experienced, the global stock of plug-in electric cars represented just one out of every 250 vehicles (a mere 0.40 per cent) on the world’s roads by the end of 2018.

Electric car deployment has been growing briskly over the past decade, with the global stock of electric passenger cars passing five million in 2018, an increase of 63 per cent from the previous year. Around 45 per cent of electric cars on the road in 2018 were in China – a total of 2.3 million – compared to 39 per cent in 2017. In comparison, Europe accounted for 24 per cent of the global fleet, and the United States 22 per cent. The number of charging points worldwide was estimated to be approximately 5.2 million at the end of 2018, up 44 per cent from 2017.

Most of these charging points were installed privately, accounting for more than 90 per cent of the 1.6 million installations last year.

Incidentally, the EV30@30 campaign reflects a policy characterised by a wider adoption of EVs, in line with EV30@30 if it were to be applied at a global scale. The EV30@30 campaign, launched at the Eighth Clean Energy Ministerial in 2017, set the collective aspiration for all EVI members of a 30 per cent market share for electric vehicles in the total of all vehicles (except two-wheeler) by 2030. Under the EV30@30 scenario, EV sales are expected to reach 44 million vehicles worldwide per year by 2030.

In 2018, the global electric car fleet exceeded 5.1 million, up two million from the previous year and almost doubling the number of new electric car sales.

In the Indian context, the year began with a bang for EV players with the government’s approval for Rs 10,000-crore programme under the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles in India (FAME India) FAME-II scheme for promotion of electric and hybrid vehicles in the month of February.

According to the Ministry of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises (MHIPE), till November, close to 285,000 buyers of electric and hybrid vehicles have benefited from the subsidies provided under the FAME-India program to the tune of Rs 3.6 billion. However, this figure seems highly inflated.

According to the Ministry of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises (MHIPE), till November, close to 285,000 buyers of electric and hybrid vehicles have benefited from the subsidies provided under the FAME-India program to the tune of Rs 3.6 billion. However, this figure seems highly inflated.

Another good news came in July with the GST reduction on EVs from 12 per cent to five per cent, which helped a lot in improving the sentiments. In the same month, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced additional income tax deduction of Rs 1.5 lakh on interest paid on loans taken to buy electric vehicles. In her maiden budget speech, the Sitharaman also underlined her plan to make India a global manufacturing hub for EV.

Additionally, the Union Cabinet also proposed customs duty exemption on certain EV parts including e-drive assembly, on-board charger, e-compressor and a charging gun. The intention was to cut down the cost of EVs in order to boost sales in the country.

According to a Niti Aayog report, India needs a minimum of 10 GWh of cells by 2022, which would need to be expanded to about 50 GWh by 2025.

The government has been tom-tomming that around 11 states have either issued or proposed electric vehicle policies till date. While Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala have their final policies ready, states like Uttarakhand, Telangana, New Delhi and Bihar have their policies in the draft stage. However, only policies are in place with no implementation.

In view of the moves both from government and industry, the electric vehicle market, battery market, and charger market are expected to witness CAGRs of 53.64 per cent, 58.86 per cent, and 59.58 per cent, respectively, during 2019-2030, according to a recent report by BIS Research.

“The government’s target for 30 per cent adoption of electric vehicles by 2030 is expected to be majorly driven by the electrification of two-wheeler, three-wheeler, and commercial vehicles in India. Lower rate of adoption of electric vehicles in the passenger vehicle segment is expected to have a limited impact in achieving these targets,” said Ajeya Saxena, lead analyst at BIS Research.

However, despite all such policy moves not much traction was witnessed in sales. Currently, EV market penetration is merely one per cent of the total vehicle sales in India, and of that, 95 per cent of sales are electric two-wheelers. While only 1,500 electric cars were sold for personal use in the last eight months, electric two-wheeler sales under FAME crashed by 94 per cent in the first six months of FY20, as per reports.

However, from the environmental point of view, despite all claims of clean transport it doesn’t mean there isn’t any carbon footprint left behind.

The journey of well-to-wheel (WTW) greenhouse gas emissions from the EV fleet is determined by the combined evolution of the energy used by EVs and the carbon intensity of electricity generation – as the grid becomes less carbon intensive, so do EVs.

Despite the comparative advantage of EVs in terms of GHG emissions, it is clear that the benefits of transport electrification on climate change will be greater if EV deployment takes place simultaneously with the decarbonisation of power systems.

Before an electric vehicle even charges for the first time, however, one key part of its power system already generates a significant carbon footprint. One really significant aspect of an EV to consider about is its battery. The material that helps power the battery is produced from various metals, things like nickel and cobalt and lithium.

Mining and processing the minerals, plus the battery manufacturing process, involve substantial carbon emissions. Lithium mining, required to manufacture the lithium ion batteries at the core of today’s EVs, has also been connected to other kinds of environmental damage. For example, there have been mass fish kills related to lithium mining in Tibet. Mines in South American lithium rich regions are consuming the freshwater supply depriving other consumers.

Even in North America, where strict mining regulations are in effect, harsh chemicals are used to extract the valuable metal degrading the environment. All this doesn’t bode well for the environment and the claims of harmless transportation.

Artice by —

Arijit Nag is a freelance journalist who writes on various aspects of the economy and current affairs.

Articles of Arijit Nag